John Humphries

Examiner for Trinity College London

Musician, Historian, Author, and Music Arranger

French Horn and Trumpet Instructor

Brass for Beginners Editor in Chief

Meet Mr. Humphries

As you will learn, Mr. John Humphries is an expert in a lot of things. We got to know him because he agreed to be the editor for the Brass for Beginners books. Editing is the job of going over every word and sentence carefully to make sure there are no mistakes, but also to make sure everything is easily understandable for the reader. Editing is a very important job. It can take a lot of time to edit something, and sometimes it’s necessary to make a lot of changes so that everything makes sense and is fun to read.

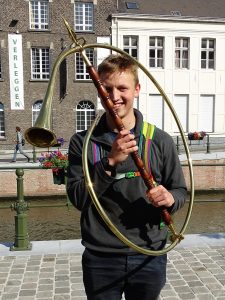

Mr Humphries is really good at editing because he is also a writer. He has written books and lots of articles for journals, which are like magazines where students go to find important information when they are studying something. Also, Mr. Humphries is really good at editing for Brass for Beginners because he is a musician and an expert in music education. He is also an expert in the history of brass (lip-blown) instruments and knows a lot about how they work. He also knows how to repair them, and even has made an instrument by himself (scroll down to see photos!).

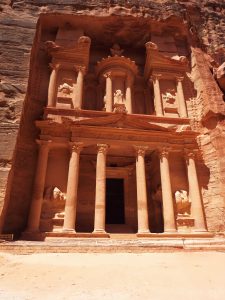

There is another thing that is interesting about Mr. Humphries. He is sort of like our prehistoric friend Ragnar, because he has travelled around the world and loves to learn new things. He likes to learn about different cultures, history, nature, and science, and is very keen on photographing all that he sees.

For all these reasons, Mr Humphries is the very best person we could have to edit our books. When you are reading Around the World in Twenty-One Trumpets, remember that every single word was looked at carefully by Mr. Humphries!

Pioneers of the Early Music Movement (center in white shirt)

With Dr. Peter Holmes and BfB Authors

Interview: Part 1

Where were you born and what are some of your fondest early memories?

I was born in Sheffield in England. We moved house when I was aged two years and two months, so anything I can remember of the old house happened when I was around two years of age. The people next door had a strange radio aerial sticking out of the side of their house. I used to try to throw pebbles at it, though I never hit it! I know I remember it, and it isn’t something somebody else told me about, because I kept it very quiet. I already knew it was naughty and that I would have been told off if I had been found out!

I fondly remember visiting my grandparents, Grandma and Grandpa Country, and Granny and Grandad Leeks, so-called because one pair had a big house in the countryside, while the other had an allotment where Grandad grew leeks. Why one pair were called “Grandma and Grandpa’ and the others were called ‘Granny and Grandad’ remains a mystery! Grandma and Grandpa Country had a railway line running at the bottom of their (very long) garden. In those days, the trains were drawn by steam-engines, and I loved rushing down the garden to see them. Granny and Grandad lived quite near to London’s Heathrow airport, and when I was a bit older, I used to love spotting the different airlines and the different makes of plane that flew overhead.

Were there any major world events that impacted your life when you were a child?

Not really, though the devastation caused by World War II took a very long time to sort out. I can remember seeing the sites of bombed out buildings, and I can just remember going to a ceremony to lay the foundation stone when they rebuilt our local church. They say that the previous church, which was completely destroyed apart from its tower and spire was a rather dull building, but the new one, where I sang in the choir is absolutely beautiful!

What did your parents do?

Dad was a lecturer in Geology (the study of rocks) at Sheffield University, while my Mum taught Geography and Geology in a school.

Do you have brothers and sisters?

Yes, I have a brother called Tom, who is a retired doctor. He lives in an old stone-built farmhouse just outside a town called Chesterfield, which is near Sheffield. He plays the guitar and the piano accordion.

What were your interests in school, can you describe your school day?

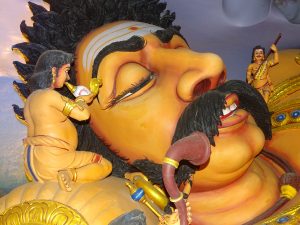

I was always interested in science, probably because my Mum and Dad were, and I was particularly keen on astronomy. I always liked music, but I never thought I was any good at it, so it is still a surprise to me that it is what I do for a living! My school day? When I was four, I went to nursery school. I could tell you quite a lot about that, but I’ll just say that we finished each morning by listening to a programme on the radio called “Music and Movement”. Mrs Oakley, our teacher, called what we were expected to do, “dancing”, but it was probably no more than jumping around. Anyway, dancing was completely new to me, and it terrified me, and although I told her that I didn’t know how to dance, she didn’t seem to understand. So, for my entire time there, I spent the last part of the morning in tears because I couldn’t dance. I still feel the same about dancing to this day, though I can disguise it better and I wouldn’t actually cry if anyone asked me to dance. Though it doesn’t happen, because I will be outta the door before they can ask! (Actually, that isn’t quite true… three or four years ago I was in Hyderabad in India during what is known as the Ganesh Festival. Ganesh is the elephant god, and each area of the town has a huge model of Ganesh, made of plaster of paris, which, after dark, is pulled around the neighborhood on a flatbed truck, accompanied by disco lights and bands of drummers. The young men (and it is mostly men) do wild dancing while the drummers play. I used to go to watch and to take photographs every night. I thought I had remained fairly anonymous, but apparently not. On the last night of the festival, several groups saw me, and pulled me into the middle of the dancing. I have to confess that I thoroughly enjoyed it. It was, after all, only jumping around!)

Now I’ll tell you what I can remember about my very first proper school. We started the day with assembly, and I suppose we must have sung in it, but the thing I remember most is that we had some percussion instruments. I think they were castanets, tambourines, a cymbal and a drum. I can’t be certain about all the instruments, but I know we had a drum. I so wanted to play that drum. I think I got to do it once, but only once! In the morning, we studied arithmetic and reading and writing. We had playtime in the middle of the morning, where we had a little bottle of milk each, and the school gave us a hot meal at lunchtime. We had fish on Fridays which I didn’t much like, and something called ‘mushy peas’ which I absolutely hated, but it came with fries, or chips, as we called them, and I really liked those. In the afternoon we did things like painting and drawing and had a mid-afternoon playtime as well. The dinner ladies used to appear at this with food left over from lunchtime – things like jam tart – but it was first come, first served, and it was a good day if you got to the front of the queue before it ran out. Something odd that I remember was that high up on one of the classroom walls was a large chart called a “Curwen’s Modulator”, which I now know was used in the 19th Century to teach singing. We never used it, but it had a strange and fascinating code on it with words like “Do, re, me, fa, and fis” on it. Many, many years later, I bought a Curwen’s Modulator at a second-hand bookshop no more than 200 yards from the school. I still have it and have often wondered if it is the one that was on our classroom wall.

Mr. Humphries’ Trumpet Treasure Hunt

Interview: Part 2

What got you interested in music, and why did you choose the French horn?

All through my childhood and my youth, I think I was inspired by my teachers, rather than by the subjects they taught, and five music teachers come to mind. There was Mrs Sterne at my infant school, Mr Courage at my Junior school and Mr Barnes at my Senior School. There was also my dear friend Keith Burdett who was my first proper horn teacher, and Anthony Baines who taught me when I was at university.

Edith Sterne was also our next-door neighbour. She was a lovely, quietly spoken, gentle person, who with her husband had come to Britain as a refugee during the War. Many years later, I learned that her uncle had been a cellist in one of Prague’s leading string quartets, and had known the composer Richard Strauss, while her husband, Franz, had an uncle called Max Brod, who was friends with the author Franz Kafka, and when he was a boy, he had met the famous composer Leoš Janáček. Not a bad pedigree for an infant school music teacher! I remember she had us all sitting cross-legged on the floor teaching us how to conduct when we were about six years old! In my mind’s eye, I can still see a line of knobbly-kneed little boys in short pants waving their arms in the air, conducting music in 2/4, 3/4, or 4/4 time. She must have taught us about note-lengths and things like that, because at my first piano lesson, my teacher (who didn’t inspire me, and maybe that is one reason why I am still a very average pianist!) asked how I knew about such things, and I told him I had learned about them at school!

Roger Courage was my class teacher, but he also took the school choir. I remember he had 90 of us singing Schubert’s “The Erlking” in unison, and him telling us to trust him, because we probably wouldn’t like it much at first, but it would grow on us. And he was absolutely right!

I could write a book about Norman Barnes. He was a brilliantly able pianist, organist, conductor, and composer, and he was also wonderfully kind and witty, and he loved wordplay. I only recently heard a new Norman Barnes story: one of my contemporaries told me about the time he and two of his friends rolled in late for a lesson. “Ah!”, said Norman, “The Three Musketeers! Must get ‘ere on time!” I suspect that many of the students at the school just thought he was mad, but to those of us who “got” him, he was an inspiration. After he died, I went to his memorial service. The church was packed, mostly with men, because it was a boys-only school, and I have never heard congregational singing like it. That wonderful sound we made was a fitting memorial to his talents in itself.

After I was offered a place at my Senior School, King Edward VII School, Sheffield, various forms arrived which needed to be filled in. One was from the school’s Music Department, asking if I wished to learn a musical instrument. There was a list of the instruments one could learn, and I remember they had exotic-sounding names, like trombone, and bassoon. I had vaguely heard of them all, but I didn’t quite know what most of them did. I knew I wanted to have a go at something, though I had no idea what. All of them sounded exciting. The one thing I did think I knew was that violins were sissy, so in my childish handwriting, I wrote, “Anything, so long as it is not a violin”. I never asked Norman his logic, but during my first week at the school, I was told I was learning the trumpet.

It was thrilling to take that old brass trumpet home with me. There was a bottle of valve oil under a flap in its old cardboard case, as well as a funny looking music card-holder-thing, and a mouthpiece. I also remember a unique, but not unpleasant smell, and blowing it seemed like fun. I remember playing “Air-trumpet” to a record of Haydn’s trumpet concerto which we had at home, so I was obviously enjoying it, but I wasn’t making much progress with high notes, and the truth was that I hadn’t worked out how to practise. Anyway, I had been learning for around 18 months when I got a message saying I was wanted in the music department. There I found Norman, along with Ralph Williams, my trumpet teacher, and they explained that they wanted to move me onto the French horn. It sounded OK to me, so I handed in my trumpet and took away a horn.

I liked Mr Williams very much, though as a brass band cornet player, I don’t think he knew much about horns. The day that Sheffield Council decided to appoint a specialist horn teacher was a very important one in my life. At my first horn lesson with Keith Burdett, I played something I thought I was very good at, but when I finished, I could see him wondering where to start. He was very gentle about it, but the trick he pulled off, which was to make me think I was about twice as good a horn player than I was, within a fortnight, was brilliant. Keith has been one of my lifelong friends, and recently he told me that what he had done was to change the position of my right hand in the bell of the horn as I played.” In his heyday, he was not only a fine teacher, but a very good horn player and a brilliant brass repairman. He got me listening to recordings of famous horn players, taught me all the famous horn repertoire, inspired me to find out about horn lore, found a decent instrument for me to play on, and the rest, as they say is history. And I found out how to practise!

Music still seemed like something I only did for fun, so I went to Oxford University to study Geology. I didn’t work hard enough to become a good geologist because I was spending far too much of my time practising the horn and attending rehearsals, and when it became apparent that my heart was not really in geology and the crunch came, the university was brilliantly supportive and allowed me to study music instead.

The course was very old fashioned. I had to write fugues and do something called Renaissance five-part counterpoint, which was scary stuff, and they assumed I would be a much better pianist than I was. The teachers, or “dons” as they call them, were incredibly distinguished, and from what I can remember, mostly very friendly, though they operated on a plane so far above my head that we had very little to talk about, aside from my essays and my dismal counterpoint exercises. There were two exceptions. One was Denis Arnold, the Head of the Faculty, who was also from Sheffield, who used to tease me that he was in awe of me because I went to a school which was generally reckoned to be somehow “better” than the one he attended, and he often joined us for lunch in the pub at the end of the street. The other was Anthony Baines.

Tony was unlike all the other teachers in the Oxford Music Faculty. He had played the contrabassoon under Sir Thomas Beecham in the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and I think that as an academic musician, he was largely self-taught. Like Norman Barnes, I suspect most of my contemporaries found him very eccentric. He was very shy, but he tried to compensate by blustering loudly while still smoking his pipe! It was obvious that he found lecturing excruciatingly embarrassing, but he was a brilliant scholar, and he wrote very important books on both brass and wind instruments. His job at the university was as the Curator of the Bate Collection of Historic Musical Instruments, a wonderful collection of instruments from the 17th Century onwards. As soon as I told him I was a horn player, he fetched the keys and opened the cases, picked out an early nineteenth century valveless horn and got me to blow it. Because I had already experimented with playing my modern horn as though it was a valveless instrument, I picked it up very quickly and was soon playing scales and trills on it. Two hours later, I found myself walking back to my college with a real 19th Century natural horn in my hand with a full set of crooks. It could not happen today, but at that moment, I felt as though all my Christmases had come at once!

Interview: Part 3

What do you like about listening to music?

Oh, Gosh! What a question! First of all, let me say that one of my pet peeves is the idea that people listen to so-called “classical” music because it is “relaxing”. Yes, it can be relaxing, but it can also convey every other emotion as well, and like all other types of music, it expresses emotions in a way which words can’t. If words could do the job, then we wouldn’t need music, would we? Also, a long time ago when I was mainly teaching brass instruments, I found myself chatting to a chemistry teacher during a train journey. He said, “but surely, you can’t actually like music if you are prepared to listen to beginners playing it badly?” Without hesitating, I replied that the whole reason I love teaching is because I love music so much that I want to help my students get better so they can love it too, no matter what strange noises they might be making at the moment. I really believe that!

What do you like about playing music?

Being a part of a team is one aspect of it. Sometimes, when you play in a big orchestra, where your own part doesn’t necessarily stand out much, you feel like you have been on a journey with other like-minded people and together you have achieved something really special which you could not have achieved on your own. At other times, when perhaps playing in a smaller group, you might get the chance to play solos, and then it is wonderful to be able to “speak” to other people through your music, to entertain and move them. And when you have really practised hard and everything goes to plan, then there is nothing better!

What is your job?

I earn most of my living as a music examiner. “A what?”, I hear you ask! Let me explain. I spend my day listening to people, mostly children, but not only children, who are learning to sing, or to play an instrument. They sing or play a set of pieces, and they also perform what we call “technical work”. My job is to assess whether they have reached the standard for the exam for which they have entered. “So, does it qualify you for a job when you have done all these exams” ? Well, no. The exams range from those suitable for players who have been learning for only a few months, right up to those suitable for people who are about to try to make their way in the music profession. “But why would I do them?” My answer to that is to try to imagine that you have set out to climb a very high and beautiful mountain, and playing an instrument well seems like trying to reach the top of a mountain when you are starting out. It could be that the mountain is featureless, and you will trudge up it, until the point where you are worn out, and it doesn’t feel like you are getting anywhere. It doesn’t feel very satisfying, and you go off to do something else. On the other hand, it might be that the slopes of the mountain have a series of fields. You work your way through the first field up to a gate which you will have to climb over. Think of the first exam as that gate. When you jumped over the gate, or passed the exam, a whole new world will appear. You are higher up the mountain, you get a better view, and because you practised walking in the first field, you are ready to go on to steeper slopes. When eventually you reach the top, you have some way of judging how far you have come! The only thing wrong with my analogy is that no musician ever reaches the top of the very highest mountain because there is always something new you can learn!

What advice do you have for Brass for Beginners students?

Remember that the reason all of play music is because we like it, and the more we practise it, the better we get and the more we like it. Work very hard, but never take yourself too seriously!

Mr. Humphries Travels the World

Bio

John Humphries was born in Sheffield and read Music at Oxford University. Subsequently he attended London's Guildhall School of Music, where he studied the natural horn with Anthony Halstead. His editions of horn music have been performed by many of the world's leading horn players, including Barry Tuckwell, Michael Thompson, Eric Ruske, Anthony Halstead, Stephen Stirling, Frank Lloyd, Javier Bonet and Johannes Hinterholzer, and his reconstructions of Mozart's incomplete horn concerto movements have been praised for their "polish, authenticity, good scholarship and talent". Recently, his edition of Paul Dukas’s hitherto unknown "Morceau de Lecture", for horn and piano, has been published by Brasswind Publications.

He is also well known as an arranger. One of his arrangements appears on the legendary London Horn Sound CD while others have been played worldwide by "The Wallace Collection", and horn sections from orchestras including the Berlin Philharmonic, La Scala, Milan, and the Bruckner Orchestra, Linz have performed his arrangements in videos which have appeared on YouTube. His arrangements for young players appear on all the main examination syllabuses in the UK.

As a writer, he has contributed booklet notes for many CDs and programme notes for hundreds of concerts. He has contributed articles and reviews for "The Horn Call", "The Horn Player", "Brass Bulletin", the Historic Brass Society Journal and the Galpin Society Journal. His book, "The Early Horn", was published by Cambridge University Press in 2000 and has been described as "a superb book" "packed with usefulness". "Rarely can anything have been written on the early history of the horn that is quite as accessible and flowing." John acted as editorial advisory board member and contributor to the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Brass Instruments and wrote articles for the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Historical Performance in Music. He is currently working on a biographical dictionary of horn players in Great Britain and Ireland before 1914, though his grown-up children refer to this extensive project as "Daddy’s bumper fun book of dead horn players"! John is also a teacher and an examiner. He lives in Surrey, England with his wife, and his hobbies include collecting brass instruments and repairing them.